Python Experiment and Intuitive Proof of Monty Hall Problem Translation

2022-08-16

Warning

The content was translated from the Chinese version by Generative AI. Please double-check the content.

Original Problem Description

The Monty Hall problem can be described as follows: In this TV show, there are three doors, and exactly one of them has a car behind it.

The audience randomly selects a door. After the contestant makes their choice, the host does not open that door immediately; instead, the host opens one of the remaining two doors that has no car behind it.

Subsequently, the host offers the audience a chance to switch their choice: the audience can either keep their initial choice or switch to the other unopened door.

Question: Which choice gives a higher probability of winning the car: switching doors or not switching?

(Description adapted from 知乎)

First, the answer: Switching gives a higher probability, 32; not switching gives only 31.

Python Experiment

Facts speak louder than words. We can simulate the scenario using Python:

import random

def which_choice_can_earn_car():

# Initialize three doors

doors = [1, 2, 3]

# Randomly select one door to hide the car

car = random.choice(doors)

# Randomly select one door as the audience's initial choice

choice = random.choice(doors)

# Doors the host can open (excluding the audience's choice and the car door)

doors_can_be_opened_by_host = [i for i in doors if i not in [car, choice]]

# Host randomly chooses a door to open from the available ones

door_opened_by_host = random.choice(doors_can_be_opened_by_host)

# Assume the audience switches doors; the new choice is the only remaining door after removing the initial choice and the host's opened door

doors.remove(door_opened_by_host)

doors.remove(choice)

re_choice = doors[0]

# Since the host always opens a door without the car, the car must be behind one of the two doors chosen by the audience. We directly check these two to determine if switching is better.

if choice == car:

return 'No change'

elif re_choice == car:

return 'Change'

if __name__ == '__main__':

# Count the number of wins for switching and not switching

change = 0

no_change = 0

# Test 10,000 times

for i in range(10000):

result = which_choice_can_earn_car()

if result == 'Change':

change += 1

else:

no_change += 1

# Output results

print(f'Change: {change}\nNo change: {no_change}')On the first run, the magical random library was kind enough to output the theoretical probability directly:

Change: 6667

No change: 3333Thus, it is clear that switching gives a probability of 32, while not switching remains 31 (I don’t need to explain that the winning probability without the host opening any door is 31, right?).

Simple Analytical Proof

Thanks to the excellent foundation of nine-year compulsory education, we can all agree on the following conclusions:

- During program execution, observing the program (e.g., outputting more intermediate steps) does not affect the result.

- The probability of initially choosing the car (i.e., winning without the host opening any door) is 31.

- The probability that the car is behind one of the two doors not initially chosen is 32.

- After the host opens a door, the winning probability of switching cannot be 31.

(The first point means computer programs do not follow the quantum mechanical uncertainty principle—this non-rigorous explanation is for simplicity.)

With conclusion 4 established, we only need to explain why switching gives 32 instead of 21.

From a Programming Perspective

Modify the code as follows:

# Initialize three doors

doors = [1, 2, 3]

# Randomly select one door to hide the car

car = random.choice(doors)

# Randomly select one door as the audience's initial choice

choice = random.choice(doors)Add an output statement to check if the initial choice wins:

# Initialize three doors

doors = [1, 2, 3]

# Randomly select one door to hide the car

car = random.choice(doors)

# Randomly select one door as the audience's initial choice

choice = random.choice(doors)

print(choice == car)Obviously, the probability of outputting True here is 31 (conclusion 2).

Since the values of car and choice do not change, this probability remains the same whether checked here or at the end of which_choice_can_earn_car.

By the end of the function, the host has eliminated a door without the car, so the car must be behind either the initial choice or the switched choice. The switched choice is uniquely determined after the initial selection and host’s door opening. Thus, the winning probability of switching equals the probability of initially not winning, i.e., 1−31=32.

From an Intuitive Perspective

The initial winning probability is 31, and the probability of not winning is 32.

Regard the two unchosen doors as a single group, which has a combined winning probability of 32. Initially, we cannot use this group directly since it contains two doors, each with 31 probability.

However, when the host opens one non-winning door from this group, we can now utilize the full 32 probability by choosing the remaining door in the group. Since局部 operations within the group do not affect its total probability, and the group now has only one door left, that door inherits the entire 32 probability.

For Extra Conviction

Scale up to 10,000 doors.

Suppose there are 10,000 doors with one car. You randomly choose one, and the host opens 9,998 non-winning doors, leaving one unopened door besides your initial choice.

Would you switch to win the car? Most people would switch, as the initial winning probability is 100001. If you initially lost (probability 100009999), switching guarantees a win. Thus, switching gives 1−100001=100009999 probability.

The logic is identical when scaling down to 3 doors.

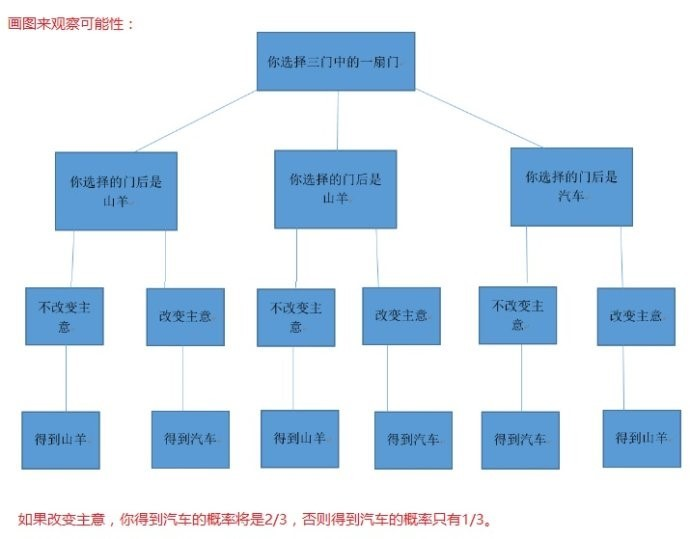

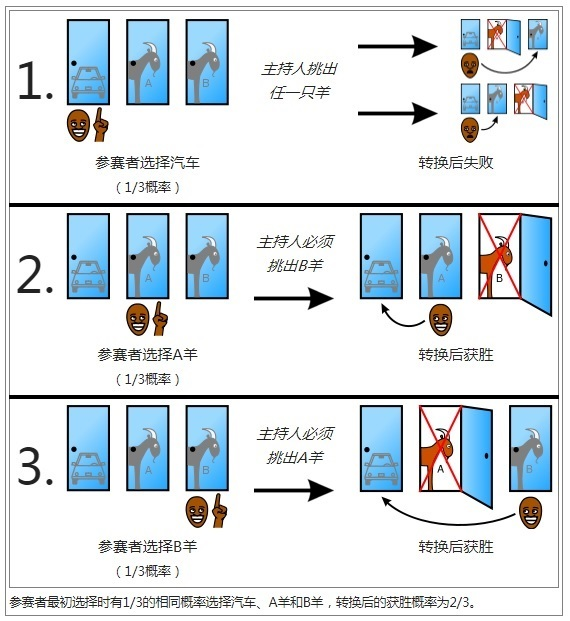

From a Simple Tree Diagram

Image source: https://blog.csdn.net/weixin_42467709/article/details/82882617